|

The Barossa Goldfield.

Part 2

At the first anniversary of the discovery of the Barossa goldfield several celebrations were held on and off the field. Most of the afternoon was taken up with different sports, but at night a dinner was provided for Warden Peterswald and attended by about 50 men. A large number of speeches were made and even more toasts were given. Among some of them were, to the gold mining interest of the Colony, especially that of the Barossa, the Land we live in and a special one to Mr Goddard, through whose enterprise the field had been opened up.

After a year, conditions on the field had not really improved very much at all. The vast majority of diggers, and most of their families, still lived in tents. Some of these tent dwellers had been on the field for almost all that time. Maria Renowden, mother of seven children, had been living in her tent for a year when she died in October. John and Emily Garie lost their son of eleven months on 12 January 1870. Albert Thomas, aged two and also a tent dweller drowned in one of the small dams which were everywhere on the diggings. He was the second child to die under such circumstances.

To make mail deliveries more regular and on time, the government invited tenders in August 1869 for the conveyance of Her Majestys Mail between Gawler and the Barossa Goldfield, which was to start on 1 January 1870. It had to be delivered every day of the week except on Sundays at a rate of travel of 12 kilometres per hour over a distance of 20 kilometres. The successful tender came from William Dailey who was willing to give it a go for 39.10.0 per year. Jane McEvoy, who had also tendered, but for 70 was naturally unsuccessful.

Regardless of the continuing primitive living conditions and the irregular gold yield, some very good finds were still made occasionally by a number of diggers, including some German farmers who went home each night. A party at Goddards Hill was offered 95 for two shares in their claim but refused to accept. They were more than happy with what they had and the prospects of getting more.

According to James Harris, a company chairman, his batteries would be able to crush 200 tons a week. During its first week of operation 280 tons were crushed yielding 297 ounces. One party obtained 35 ounces from 19 tons whereas another party got six ounces from 25 tons. Several other parties and individual diggers also had extraordinary results.

After another round of Christmas festivities and New Year celebrations, most miners returned to the field in 1870 to continue where they had left off. With the New Year also came the need to buy new yearly licences which were now going to cost ten shillings a year, a far cry from the 30 shillings per month paid by the early Echunga diggers.

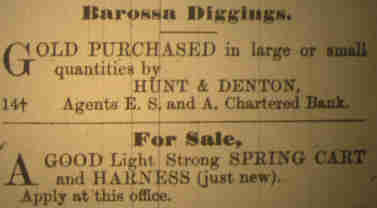

Once the diggers got back to some serious work many found enough gold to be more than happy. The Victoria Crushing Company had averaged a yield of one ounce per ton of ore, which had amounted to more than 700 ounces after only six weeks. Early in November Wilcox had bought 160 worth of gold, including 30 ounces from Springbett. By the middle of January 1870, as many as 53 ounces of gold were displayed in J. and G. Wilcoxs window in Gawler.

More good news was reported during the first week of January when it became known that 67 tons of cement from Job Harris had been crushed yielding 130 ounces. They sold it for more than 500. The ESACB had also been busy. It had bought as much as 400 ounces from the diggers. By the end of the first month the Victoria Gold Quartz and Cement Crushing Company had processed more than 700 tons of cement yielding just over 700 ounces of gold.

Still, it was not enough to pacify the Gawler Times. According to its editor the government had not shown much energy or common sense as far as local diggings were concerned. For many years he said, the nature of its regulations had operated as a bar to the diggers enterprise. Although it had recently decided to issue half yearly licences for five shillings each, they were only issued for set calendar dates starting from 1 January to 30 June. If a licence were taken out on 1 June, at five shillings, another one would have to be paid for from the next period starting on 1 July. He would like to see a monthly licence fee of one shilling, or better still, no licence at all but a tax on gold.

Although January had some extremely hot days accompanied with strong wind and dust storms, ripping up a number of tents at Victoria Hill, it did not stop the work of the crushers or the accumulation of gold. During the first week of February Wilcox bought 52 ounces and the Victoria Crushers had produced 805 ounces so far from just over 1,000 tons of cement. During its first 16 months the Barossa goldfield had produced nearly 11,000 ounces of gold worth 42,000.

A new rush to Hisseys Gully had started as well as one near Spike Gully, not far from where the El Dorado Company had opened up a reef. With harvesting and other agricultural jobs well and truly finished and it still being too early for wheat sowing, more men came back to the field. After a few heavy downpours most dams were filled and many prospectors were lucky picking up surface and alluvial gold. Britcher now decided to build even larger crushers to process the additional ore being dug up all over the field. His improved and larger crusher was started in February 1870.

Regardless of all the good news and the better prospects, a number of miners left for what they perceived to be even better prospects. In February several diggers left for the fortunes of the just discovered Blumberg field. Other diggers tried the head of Spike Gully and more than two dozen men were still at work on the Moonta Flat. James Goddard and party struck another fine patch of gold on Victoria Hill and the Kapunda Gold Mining Company declared a further dividend of 12 per share.

The largest problem on the field though was still the availability of water, or rather the lack of it. Although there had been a few good rains during the past months, they were far from adequate for the many diggers trying to use their puddlers, cradles, rockers or just a gold pans. The two companies operating crushers needed still more water and even after the completion of several dams they had to stop their machinery in April because of the lack of water. The Gawler Times was convinced that if water and money were available the reefs at Barossa would prove more productive than many of those in Victoria.

By late autumn and the start of heavy winter rains, much better results were obtained. Both crushers were at work again and during the months of May and June they crushed a total of 950 tons between them. Most people were in good spirits and even the town of Barossa was rallying from its partially deserted appearance. A new bakery had been added as well as two butchers.

A group of five industrious and hardworking Afghans had also taken up a claim and were doing extremely well. In August they had five tons crushed, which yielded more than four ounces. They were still on the field in 1873 when The Guardian imagined that these powerful men would be very suitable for employment on the Northern Territory Reefs. At the start of July the ESACB published the kind of information wanted by many people, namely the amount of gold it had bought during the last few years at the Barossa goldfield. Up to the end of 1868 the bank had bought 997 ounces.

During the next six months up to 30 June 1869 it bought 558 ounces and during the next half year a further 2,526 ounces. The last available figure was for the first six months of 1870 when as many as 1,169 ounces were sold to the bank. In addition to these amounts it had bought gold on other fields as well. A total of 613 ounces came from the Onkaparinga, 462 from Echunga, 390 from Jupiter Creek, 266 from Mount Pleasant and 29 ounces from South Rhine.

Some other interesting figures were published on 24 September when it was revealed that the Barossa field employed a total of 465 diggers, eight carters, ten men at the crushers, one doctor, one policeman, five storekeepers, seven innkeepers, two bakers, two shoemakers and four butchers. There were also 150 women on the field as well as some 300 children. However there were not enough at Victoria Hill to make it feasible for Kaeshagen to keep his butcher shop open and he relocated to Barossa.

Towards the end of August 1870, a large public meeting was held at Victoria Hill. Among the motions carried by the miners was that the government should be pressed to organize prospecting parties to discover new fields. They also wanted to see rewards made of between 1- and 40 for the discovery of new grounds. Finally they wanted some repairs made to the roads and bridges in and around the diggings.

Among the 465 diggers were still a large number who had no idea about alluvial mining. There were also those who did but had neither the money nor the patience to do the work properly. Needless to say that accidents did occur regularly. Edwin Lear met with an accident while working his claim on Victoria Hill. A large quantity of stays gave way, knocking him senseless and burying him beneath it. Luckily his son, being at hand, procured assistance and got him to his tent where he was attended to by Dr Smith.

This was the second accident of such nature. Only a few weeks before Stephen Brooks broke his leg when his stays came down. Another digger, on his way to the post office at Victoria Hill, fell in a 30 feet hole and broke his collarbone. Doctor Smith on his way home, after having attended to the digger also fell in a hole but escaped injury.

A far more serious accident occurred in February 1871 when William Hamlin, the original discoverer of gold at Humbug Scrub, was crushed to death by a fall of earth in his Kapunda Hill claim. He left a wife and three children to miss one whose happy face and cheering words have tended so greatly to attract esteem and affection.

Life on the goldfields could be dangerous and short for children too. Among the deaths recorded by W.H. Rosman was Edwin Robert Munyard, the small son of Edwin Munyard of Wash Hill who died of severe burns after falling in a dish of boiling water. This was the seventh case of death on the diggings so far. Elizabeth Harris, daughter of Job Harris died at Sandy Creek, aged five years, on 17 June 1869. Two year old Albert Thomas, son of Richard and Hannah Scown, drowned in a deserted claim in December 1870.

By the end of 1870 James Goddard was given command of a number of government prospecting parties. Many observers and interested diggers in particular, were convinced that with such a veteran digger at the helm there was no question as to the ultimate result. So far the Barossa field alone had produced a yield of at least 10,000 ounces, as against 8,000 ounces the year before. The money realised from their sale, distributed amongst the industrious plodding diggers, would have been of great benefit to them and those dependent on them.

It also saved scores from claiming assistance from the Destitute Board. There was now a steady population of about 400 men on the Barossa goldfield and a total population of about 1,000, which included women and children. It was enough for the residents to ask the government for some facilities normally available in small towns.

At the start of 1871 it was reported that about 45 tons of ore had been put through the crushers at the end of 1870, yielding some 25 ounces of gold. During 1871 work continued at Hisseys claim and at Hatchs gully but the Victoria crushing plant remained idle. Even so, it was estimated that more than 2,000 ounces of gold had been sold on the Barossa diggings during the first three months. When the winter rains came down again it provided ample opportunities for prospecting new and old grounds, particularly at Green Hill and Goddards Hill.

The government contracted Charles Agett to build a dam at Nuggetty Gully and in Moonta Gully. In several other places prospecting flags were blowing in the wind with many men, women and children at work. With prospects looking much better a miners meeting was organised at the Old Spot Hotel, chaired by W.H. Rosman. This time it was hoped to get the government to pay for additional prospecting of the Barossa goldfield and in particular to recover leads successfully worked to certain points and then lost.

Towards the end of May enough cement was available for the crushers of the Victoria Company, directed by James Harris, to restart work but most miners were taking their cement elsewhere due to the increased charges. When the dams at Nuggetty and Moonta Hills were completed, Clark & Co constructed a puddling machine. At the same time a few government prospecting parties had found a little gold.

By September however, it was thought by many that the Barossa was done but, said its local reporter, knowing how a goldfield, down to its veriest zero, suddenly rises, Phoenix like, to a previously unattained position of prosperity and production, we are content to wait with fortitude, trusting to the strong arm of the miner in due time to strike some fundamental source of our subterranean wealth, which shall attract a larger number of his class than ever amongst us, and demonstrate to the capitalist the safety and profitableness of gold mining as an investment.

On 5 October 1871 the third anniversary of the discovery of gold at Barossa was celebrated with an evening of entertainment at the Institute. Warden Peterswald presided and gave an appropriate address. There was much singing, recitations, music and a talented performance by the Gawler Christys, followed by a very successful ball that lasted until the early hours of the next morning. During that evening it was reported that gold to the value of 160,000 had been raised so far, all of which had gone into the pockets of the workingman and there was still plenty of gold left.

The Barossa goldfield, though very quiet at times, still recorded some 46,000 ounces during these early years, not including amounts sold to storekeepers, publicans and banks in Adelaide or Melbourne. By the end of 1871, the estimated value of gold production from the Barossa goldfield was 180.000.

As the total value of gold produced at the Barossa and other goldfields in South Australia had now well exceeded 500,000, it was once again moved in parliament that the discoverers of the Barossa goldfield were entitled to some reward. However the government quickly pointed out that rewards of 5,000 would not be paid until all conditions set out in the regulations had been complied with. The two most important being that 500 persons should have taken out a licence and 10,000 ounces of gold had been raised within the prescribed time.

At the start of 1872 it was reported that the Barossa goldfield was suffering from an unprecedented depression, with a fair prospect of a frequent recurrence of that state of things as the patches of alluvial ground opened from time to time became worked out. Something had to be done to revive the place as its existence as a goldfield depended chiefly upon an energetic system of prospecting, it was said. However such was the universal opinion of the diggers, and in their present mood it would not be their fault if the result was not satisfactory. We look to Parliament to provide the means.

This time the government relented and promised some financial assistance. Two weeks later the same paper stated that mining matters had fallen into a state of insipid dullness, which was only relieved at times by small discoveries, reminding every prospector and digger that not all gold had been found yet. It was also hoped that the promised government grant for prospecting would not be too small and not too long in becoming available.

Six months later it was still very quiet on the Barossa diggings and the Victoria Crushing Company was wound up, selling its machinery by auction. The plant and machinery consisted of a steam engine and a 15 head stamper, in three batteries, complete with standards and stamp boxes. With it came some 300 tons of firewood, tools and stores and a lease of 80 acres, which still had a few months to run. The whole lot was sold at 1,210.

If this was not bad enough, Frederick Hannaford removed Britchers old crusher as well. Finally the government also decided to remove Constable F. Goldney and sell the police building leaving only one store still operating in Barossa. It remained quiet for more than a year when a new rush took place at Hisseys Gully. This time William Malcolm and James Goddard banded together and within a short time were successful in finding more gold. They formed the Malcolm Gold Reef Company, which after a short time found a rich deposit of copper.

In June 1873 the Central Barossa Gold Reef Prospecting Company was formed. It was made up of 160 3 shares, which were available from Charles G. Ive, broker of King William Street, Adelaide, who was also secretary of the Adelaide United Gold Prospecting Company. By the end of 1873 several companies were still operating, more or less, at Barossa. Among them was Hisseys Gully Gold Mining Company with eight claims adjoining Malcolms Company, which employed 36 miners. Although they were neighbours, relations between these two companies were not always friendly.

Among other companies still active on the Barossa field was the Caledonian, the Gawler Gold Mining Company, where Job Harris was doing his utmost to make a success of it and the Montaceena, a company from Saddleworth. There were also the Walkerville Gully Company, the Victoria and Albion Prospecting Company, which held claims on Moonta, Red and Edwards Hills.

For the next few years gold mining at Barossa was certainly a low key affair. Although several more discoveries had been made at Barossa, and in some other parts of South Australia, the official total gold production recorded for 1875 was only 1,656 ounces. Not too much of it had come from the Barossa goldfield. The fields remained fairly quiet though. Those men still at work mainly stayed because they had nowhere else to go.

With the reduced population, most of the businesses had closed except the hotels. E. Martin of Gladstone still operated a hotel of sorts, as did J.H. Loftes of Little Para and Job Harris of the Sandy Creek Hotel. After some years, most of the previous thousands of Barossa diggers had drifted back to their old jobs, or other fields. A few tried their luck at Mount Pleasant and Blumberg. Some remained, including Thomas Hissey.

There was no production recorded officially for 1877 from the Barossa field and a year later there were only 288 ounces recorded. In 1878 a small number of men were still digging at the Barossa, Yatta Creek and Humbug Scrub fields and M.R. Morton of the Southern Cross Hotel had been able to buy some fine specimens from these diggings. In 1879 the grand total amounted to 21 ounces and in 1880 there was once again no officially recorded production at all.

Early in 1880 there was a new rush to the Barossa goldfield after some encouraging finds and by March about 20 men were still at work and making good wages. To make processing of gold a little easier and cheaper, William J. Thompson proposed to build a water race from the Para River, near Williamstown, to the Barossa diggings.

A number of new companies were started up in 1881 when there was a renewed interest in gold mining in South Australia and several old mines and fields tried again. The Grunthal Gold Mining Company had started work on its reef after its directors had visited the site and picked some coarse gold from the rock. By June 1882 it had dug three shafts, all of which were bearing gold, according to the mine manager.

The Barossa goldfield, which had seen South Australias largest gold rush up to that time, had given rise to three towns and provided long term employment and income to a large number of people on the field and in the surrounding towns, especially Gawler. It remained rather quiet for a number of years until 1886 when spectacular finds at Teetulpa and some new technology resulted in a renewed interest in the old Barossa diggings by those unable to go Teetulpa.

After the initial rich strikes at Teetulpa had lured its thousands of hopeful diggers, storekeepers, promoters, investors and speculators, gold digging at Barossa was once again resumed and continued for a long time yet. Some small shows and a few very large ones, such as Menzies Barossa, would dominate the headlines for some considerable time. Even today there are still many people convinced that there is gold in them Barossa hills and valleys yet! Only time will tell.

If you would like to find out more,

|